In 1971, I was hired right out of college as a staff member of the newly founded Institute of Policy Sciences and Public Affairs at Duke University. My job that year was to complete a photographic study of substandard housing and living conditions in North Carolina. I traveled throughout the State for ten months with my 35mm camera. Looking back, I see this project as an opportunity for a young southerner actually to get to know something about the South by looking in depth at one southern State, by meeting and talking with people in their homes, and by making portraits and landscapes throughout the State. In completing this body of work, I was also following the dictum of my teacher Walker Evans who told his students to avoid as much as possible the influence of the classroom and the museum, to have their work spring from what he called, “the life of the streets.” For a young man learning how to be a photographer, I couldn’t have had a more important street to explore.

In 1972, a selection of these photographs was exhibited at University of North Carolina Symposium on the South, “The Mind of the South and The Southern Soul” as well as at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art. In 1978, ten of these photographs were also published in I Shall Save One Land Unvisited by Jonathan Williams and were part of a traveling exhibition opening at the Corcoran that same year.

A Southern Dream

In the fall of 1971, I was just out of college and beginning my second education as a photographer. For one year, I traveled throughout North Carolina with my Nikon camera and Tri-X film. I had an assignment from the newly formed public policy program at Duke University to photograph substandard housing and living conditions in the state. This was an opportunity for a young, Atlanta-born southerner to become aware of something about the South beyond the suburbs by looking in depth at one southern state, by meeting, photographing, and getting to know people in their homes and dwellings, and at work in the fields.

Every photographer hopes to create a distinctive body of work, no matter at what stage in a career, to discover a way of seeing and photographing that is uniquely his or her own. But none of us can avoid the pictures we carry with us in our minds from photographers who have come before. As I wandered around North Carolina, I was fortunate to have good influences.

On Wolf Mountain near the Tennessee border, Dorothea Lange’s driver “Ditched, Stalled and Stranded” in the San Joaquin Valley of California in 1935 appeared to me in form of a young man posing on the hood of his jeep (photo #8). His home had burned down the week before. A group of migrant workers throwing horseshoes on a summer evening after picking potatoes near the Carolina coast (photo #11) might have stepped off the joyful pages of Eudora Welty’s 1930’s Mississippi in One Time One Place. Not far from that game of horseshoes, I found Robert Frank’s Beaufort, South Carolina jukebox from The Americans (photo #6). But instead of Frank’s baby lying on the floor, a young man peered in the open window just as I took the picture. The day I framed the tired, lined face of a Sampson County field worker staring back at me below the brim of his upturned cap, Walker Evans Walker Evans was looking over my shoulder (photo #16). And who would have guessed Gary Winogrand’s street smarts would come in very handy as I photographed farmers at an auction in Sampson County in the summer of 1972 (photo #121)?

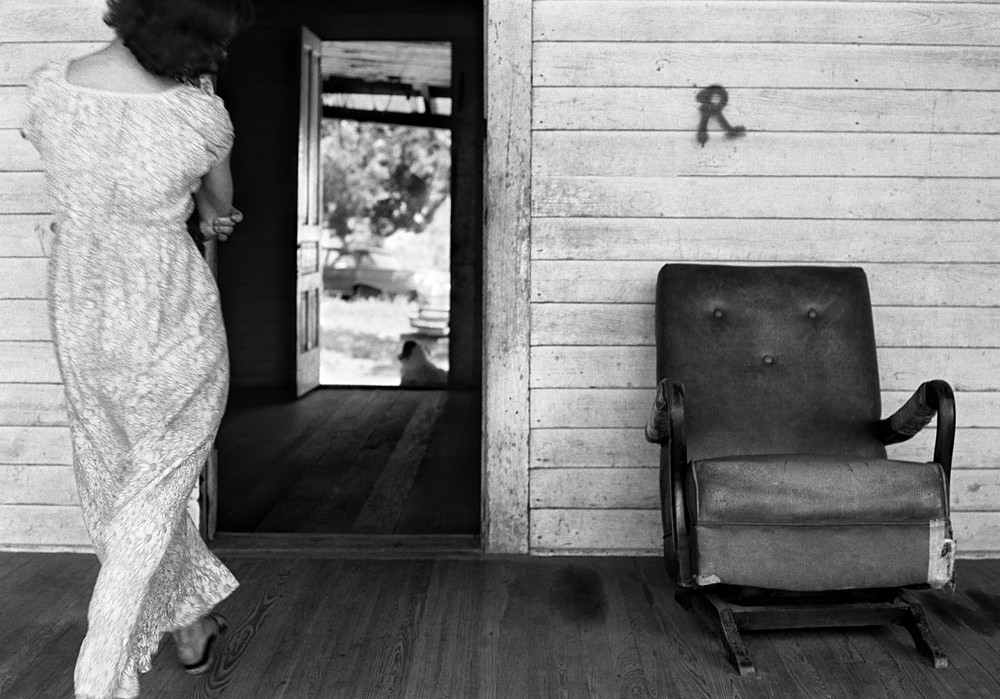

Later that summer I made a photograph I can’t trace to anyone else.

The house was wood framed, dirty white wall boards, patched vinyl chair, refrigerator with door ajar and guts displayed, oil stained porch floor – the whole structure fifty years past its prime, held up by cinder blocks, stones, and a few rough sawn beams. She couldn’t have been more than eighteen years old, nineteen tops, brown hair, square jaw, clear skin, in a long, daisy-patterned cotton dress, cat-eye glasses and sandals. She listened patiently, holding her toddler boy – the youngest of three children – on her hip, as I explained why I was there.

“I am working on this project, making photographs of the kinds of houses a lot of people in North Carolina have to live in…”

While I spoke she glanced back at her house and at her other son and daughter playing with the dogs by the wide-open front door. She seemed to be considering if she lived in the kind of run-down house I was describing. When I paused she looked back at me, eyes squinting in the noon North Carolina sun, and said, “Ok if you want to take pictures, go ahead.”

So I did. I took five or six shots that went nowhere. I had been counting on the family to stay close together there on the porch, but after a few minutes, the other children wandered inside and even the dogs abandoned the scene. At the time, I didn’t have much experience as a photographer, but I knew when the pictures weren’t going to get any better. I thanked the young woman and said goodbye. As she turned, still holding her son, to follow her other kids back inside, I lifted my camera and made one more exposure. This one is like a dream. It’s a southern dream any of us could have. It is the bare bones of a story we can only imagine. A woman of indeterminate age strides towards an open door. She walks with purpose and grace – left foot forward and poised above the floor, her child hidden from view but there in her tight embrace. She is our mother, perhaps the Madonna protecting the child that will one day save us all. But for now she is walking past a large spray-painted letter, a black cursive R. R for Reap, Rejoice, or Repent? Below that R, an old brown chair radiates so much personality its three buttons form the eyes and nose of a face, with a dark smiling mouth in shadow below. A benevolent God in disguise? Perhaps that was R for Rapture? She is walking from light into near darkness. Three strides beyond is second door where we see framed dog, a junked car, and part of a tree shading a dazzlingly bright yard. From light to darkness and back into the light.

This is my own moment; perhaps the first time my camera pointed me towards thrilling possibilities of photography to connect with our unconscious minds, to suggest knowledge beyond words. For the last four decades I’ve searched for these moments, never anticipating when they might materialize, the kinds of rare moments that appear only in photographs. Or in dreams. Alex Harris - January 2016